Image credit: Unsplash

Since 2017, California has taken action to spur housing production. The Legislature has passed nearly 100 new laws to facilitate the construction of new homes, which includes requiring cities to update local housing plans with better production targets. The state’s executive branch has pursued incentives to reward cities that are committing to addressing the housing crisis and penalizing those who are not. The attorney general scored recent victories in legal conflicts to advance plans for housing in wealthy cities such as Malibu, Huntington Beach, and La Cañada Flintridge.

However, California’s approach to reform has not had the tangible impact seen in other states, such as Texas, and in countries such as New Zealand. Those locations have significantly changed their land-use regulations and expedited construction by preventing local governments from denying permits through other means.

Meanwhile, California must still prepare to reach its 2022 goal of building 2.5 million housing units by 2030. In recent years, around 110,0000 units have been permitted annually. Updated plans across the state have included zoning changes to allow for roughly 750,000 new homes. The state estimates that more than 6,500 pending developments have been unlocked due to oversight. While progress is made, more is needed to improve affordability and stem population losses driven by the high cost of living.

Malibu, for instance, needs to catch up on its mandated housing plan, which was due in 2021. Malibu eventually settled with the state after the attorney general asked the courts to intervene and has agreed to adopt a compliant plan by mid-September.

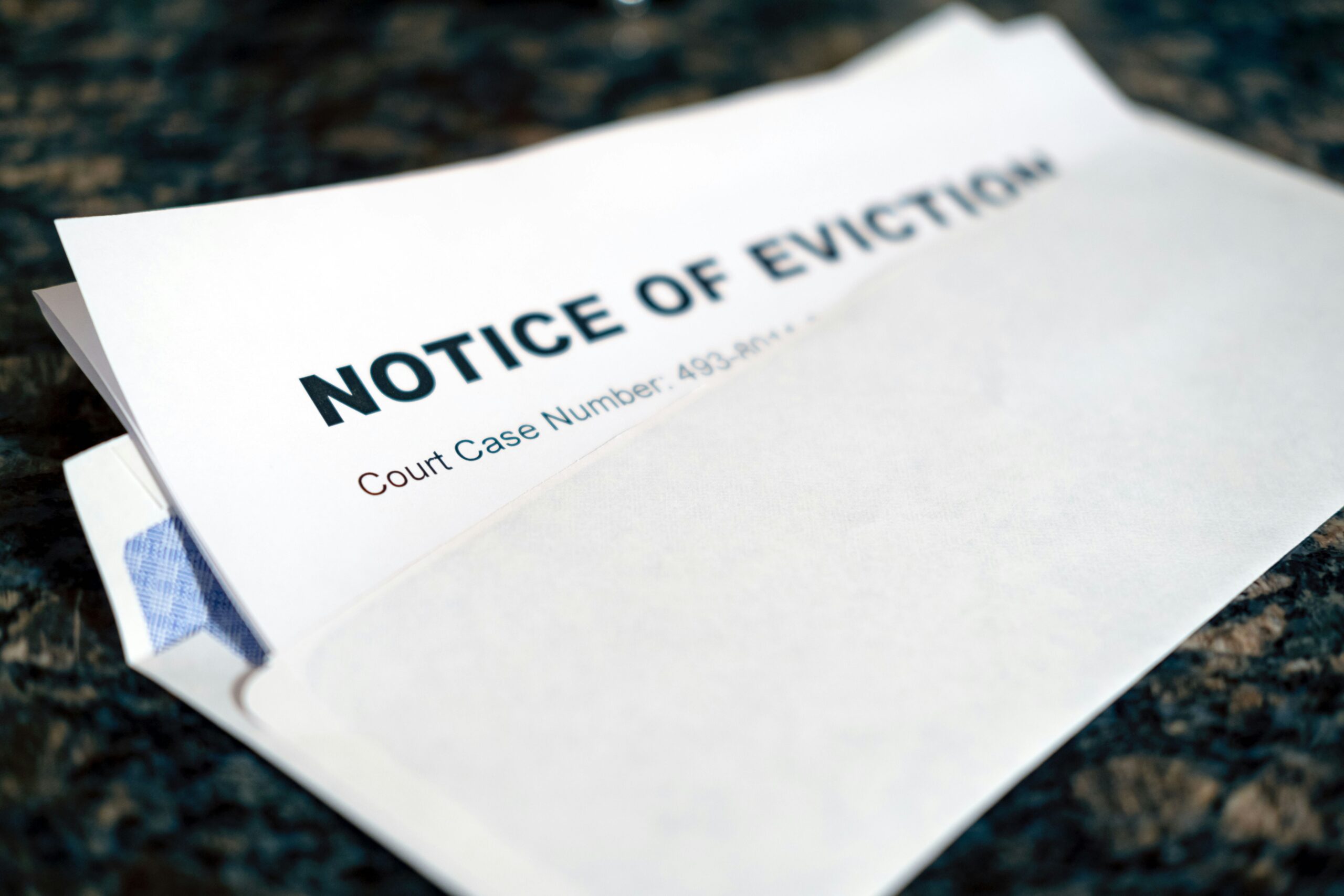

The city of Malibu isn’t alone, though. Nearly a quarter of Southern California cities lack state-approved plans to accommodate new development and implement fair housing policies. As a result, the region’s residents suffer the effects, from high rent and overcrowding to even eviction and homelessness.

Senate Bill 1037 from state Senator Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco) would work to give existing laws more force. Legislators could also strengthen the builder’s remedy laws to incentivize cities to create compliant plans that would allow specific projects to bypass zoning rules, providing more clarity for developers.

Resistance from towns is not the only obstacle the state faces. The state-mandated housing plan framework also bears some responsibility, as it has allowed cities to change zoning up to three years after finalizing their housing plans.

Another source of delays is the California Environmental Quality Act, which requires the review of zoning proposals for the potential for environmental impact. This means many new housing development opportunities will not be available until nearly halfway through their eight-year planning period. New housing on built-up urban land helps to reduce air pollution and greenhouse gas emissions by allowing people to live closer to jobs and amenities.

California is earning national recognition for its action on housing, partly due to high-profile state-local conflicts seen in the Malibu case. The Legislature and governor have taken on tough fights, but some view delays as inadequate.